For this trip, we flew into Denver for a 10-day loop through Colorado. Originally I tried to rent an FJ Cruiser because I knew we’d be facing some pretty rough roads up in the mountains. Well, there are no rental agencies that have FJ’s, but it turns out Toyota rents them directly! There is only one dealer in the Denver area that does rentals, but they did not return any emails or phone calls. A little research and I found out why – there are a ton of online reviews about their poor service.

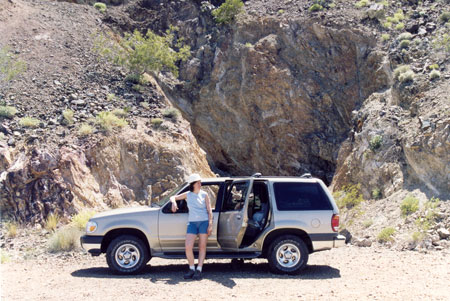

So we settled for a 4-Runner from Budget. It handled every road admirably, although we did get passed on one particularly bad stretch… by an FJ Cruiser. 🙂

Picking up the 4-Runner

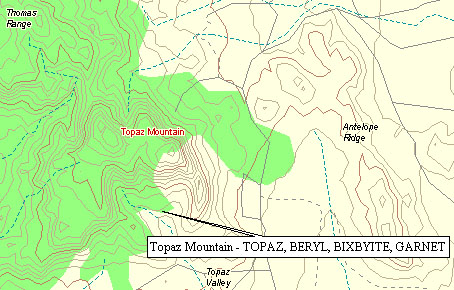

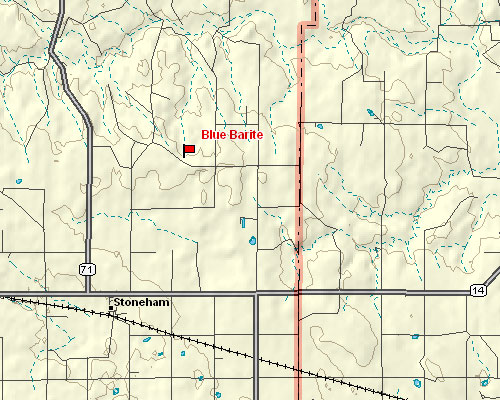

The first site we wanted to hit was blue Barite near Stoneham, so we headed out onto the plains northeast from Denver to the town of Sterling – that was the nearest motel.

Dinner the first night was limited to the fast food joints still open after we arrived, but it turns out the food from Taco John’s was surprisingly good. I can strongly recommend the Super Potato Ole’s if you find yourself in the upper Midwest or on a military base, where most of their joints are located.

October 2nd

This morning we started out from Sterling and made the short drive west to Stonham. This entire region of Colorado was once buried under volcanic ash from mountain building events in the Rockies.

All of this material has been eroded away leaving the flat plains, except for a spot just north of Stoneham called the “chalk cliffs”.

Chalk Cliffs

The cliffs are not actually Chalk, but Clay. Within the Clay there are layers of Shale and Calcite, and within these, hydrothermal solutions have deposited Barite. Unfortunately, the talus from the eroding Clay has completely buried and hidden any Shale strata. There are plenty of blue Barite crystals to be found on the surface, but it is very tough to find any Shale/Calcite/Barite matrix specimens.

After a couple hours here, we continued west and up into the mountains above the town of Lyons.

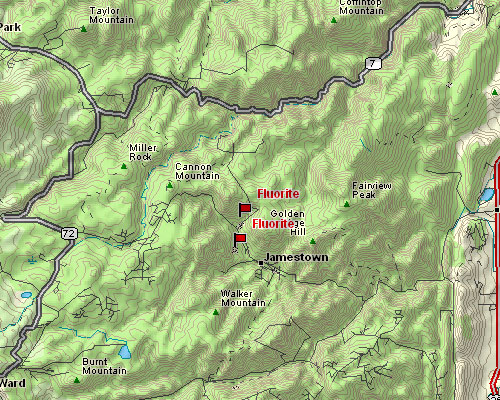

We hit the mining area near Jamestown looking for Fluorite, but found that all the mines but one were in the process of reclamation. The one remaining – the Emmet Mine – is an open pit almost completely covered in Purple Fluorite, but almost all of it was weathered to a powder, so it was hard to find any good crystals.

After the Emmet Mine, we headed north through Rocky Mountain National Park, and then south to the town of Hot Sulfur Springs, were we had dinner and stayed for the night at the Riverside Hotel.

Update – The Riverside Hotel was foreclosed in mid 2010. Check the current status before you plan a trip there!

October 3rd

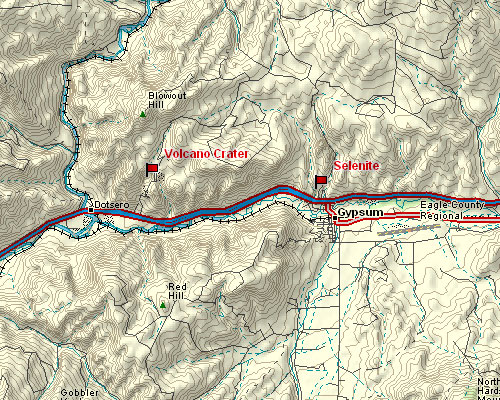

From Hot Sulfur Springs, we continued south on the back roads from Kremmling to State Bridge, then down route 131 to Wolcott, and along I-70 to a site just north of Gypsum with Selenite crystals.

Just north of the freeway is an area with very twisted strata of Gypsum and Selenite. Small crystals are all over the area, but we found the best pieces in two boulders that had fallen down from higher up on the cliff face.

Selenite Locality

Gypsum Strata

Selenite Containing Boulders

Just down the road from the Selenite locality is a fairly recent volcanic crater. “Recent” in this case means only 4,200 years ago. Reportedly, early cartographers used the crater as a reference point for their maps, labeling it “Dot Zero”. Today the nearby town carries the slightly worn-down name of Dotsero.

Dotsero Crater

The crater itself is about a 1/2 mile across and 1300 feet deep. The remnants of a lava flow can be found just down the hill.

We continued south for the rest of the day and stayed in Gunnison that night.

October 4th

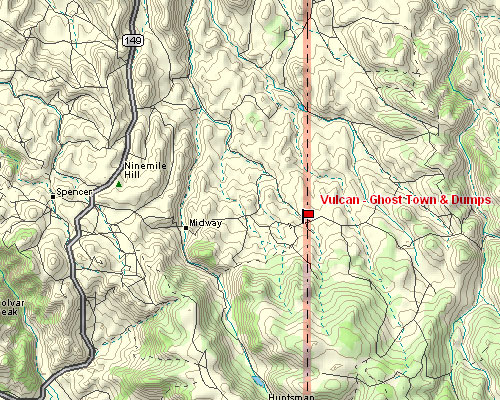

Leaving Gunnison after a huge breakfast at the W Cafe, we headed south for a bit on Colorado 149 to a small collection of ghost towns and mine dumps along the “Gunnision Gold Belt”.

The first ghost town going from west to east, Spencer, has been mostly replaced by a ranch. There really isn’t much evidence left of mines or old buildings.

Remains of Spencer

The last one, Vulcan was unreachable because of gated private property along the road to get there. The middle one, Midway (appropriately enough), was all we could get to.

Midway Mine Dump

We checked out one dump and one prospect hole, but didn’t find much there beyond Malachite.

After this, we visited the Black Canyon of the Gunnison and then drove south to Ouray and the Box Canyon Lodge, our home for the next four days.

October 5th

We started out today by taking US-550 south, over Red Mountain Pass to Silverton. The snow started falling as we passed 10,000 feet.

Red Mountain Area

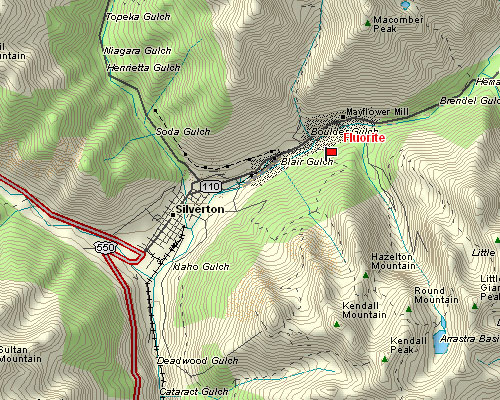

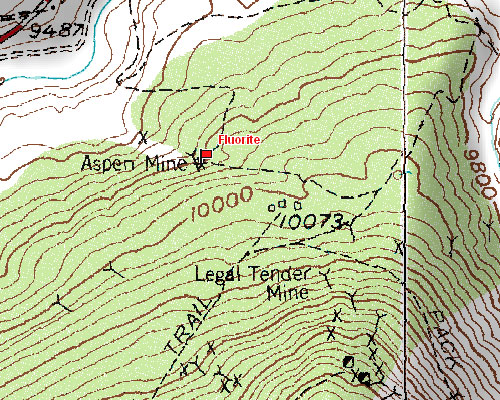

Our first rockhounding stop for the day was the Aspen Mine, just above the Animas River, a few miles from Silverton. Rockhounding Colorado lists this site as having Fluorite octohedrons.

The first obstacle is a stream that has to be forded. Fortunately the water is less than a foot deep this time of year – could be a real challenge during spring runoff.

Crossing the stream

On the way up, we passed the old tram line that runs from the Mayflower Mill down in the Animas Valley up to the Mayflower & Shenandoah Mines, perched on the mountainside at 13,300 feet.

Tram Tower

Many of the ore buckets are still present – hanging from the old cables. Not only did these bring ore down from the mine to the mill, but it is generally how the miners rode to work in the morning. Not a practice of which OSHA would have approved.

Tram Bucket

We got to a spot in the area with a few old buildings and an ore chute from the Legal Tender Mine, higher up on the hill, but the road to the Aspen Mine was not obvious.

Aspen Mine Building

Ore Chute

We finally located the road to the Aspen Mine – it was overgrown with pine trees large enough that it seems no one had come this way with a vehicle for at least 15-20 years.

After hiking down, we found the old mine entrance had been covered completely by a rock slide, and there was a decent amount of water flowing out from where the entrance would have been. This water has completely flooded a second access road lower down, and turned the top level of the dumps into a swamp. The water then forms two little waterfalls flowing down the face of the tailings pile. You can see the collapsed entrance just above and to the left of the tailings in this pic.

Aspen Mine Tailings from Animas Valley

After negotiating the water hazards, we found some pretty pieces of white Quartz with Pyrite and Bornite, and one nice round cluster of clear Quartz crystals. However, there was not a single spec of Fluorite to be found.

Later research proved that while the mine we were exploring was indeed the Aspen Mine, the book that said there was Fluorite here got it wrong. The Fluorite is to be found higher up on the Legal Tender Mine and in the chute coming down from that mine. Unfortunately, we didn’t figure this out until later, and had no opportunity to go back. Something to check on a future trip!

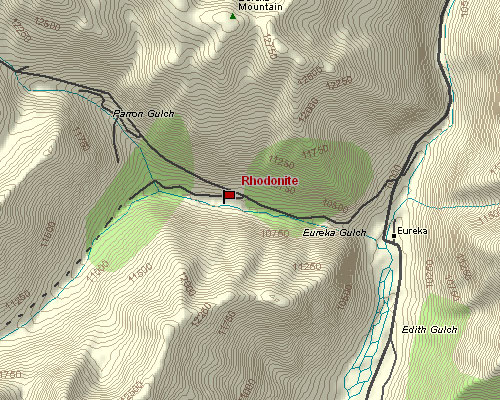

The next stop was further north up the Animas Valley at Eureka Gulch.

The remains of the Sunnyside Mill are located here at the foot of the gulch.

Sunnyside Mill Ruins

We took the road up behind the mill looking for Rhodenite. This road goes all the way up Eureka Gulch to the Sunnyside Mine and the remains of Lake Emma, which disappeared one day when a plug of permafrost under the lake melted and drained the entire lake into the mine. However, it started snowing pretty hard about halfway up, so we decided to just stop and look along the road. We did turn up two decent pieces of Rhodenite that must have fallen from the many trucks that carried ore down from the mines over the years.

View from above the Sunnyside Mill

Where we found the Rhodenite

That was it for rockhounding on this day, but we continued north up the Animas Valley to the ghost town of Animas Forks, which seemed to look oddly appropriate shrouded in falling snow.

Animas Forks

After this we took the road towards Engineer Pass and down to US-550 just south of Ouray. The plus side of this route is the spectacular alpine tundra scenery at the summit of the road.

Near the Engineer Pass Turnoff

Alpine Meadow near Mineral Point

The minus side is the last three miles coming down the mountains towards 550. The road quickly degrades to an E-ticket ride. We later checked it out in a 4-wheeling guide and found it rates an 8 out of 10. The photo here is not an action shot – the truck was relatively stable in this two-wheels-on-the-ground position, at least enough for me to get out and take the picture.

What Fun!

October 6th

After the trials of rock crawling the previous day, we took it easy today – did some shopping in Ouray and then hiked up to Cascade Falls (only a 1/2 mile from the end of 6th Avenue in Ouray).

Cascade Falls

Cascade Falls

After lunch we visited Box Canyon Falls (also within the Ouray city limits) and their large indigenous Chipmunk population.

Slot Canyon at Box Canyon Falls

Chipmunk #1

Chipmunk #2

October 7th

First order of business today was to follow the Camp Bird Mine Road all the way up to Yankee Boy Basin. Lots of waterfalls and nice scenery up here.

On the way back down we stopped at the very large tailings piles of the Revenue Mine. This is marked on most maps as the town site of Sneffels, now a ghost town with only one or two bulidings. At it’s height, 3,000 people lived here, more than three times the present population of Ouray.

We found good Galena, Quartz, Pyrite, Fluorite and Sphalerite pieces here.

Revenue Mine Tailings

In the afternoon we drove over Ophir Pass and into Telleride, but didn’t do any more rockhounding for the rest of the day.

October 8th

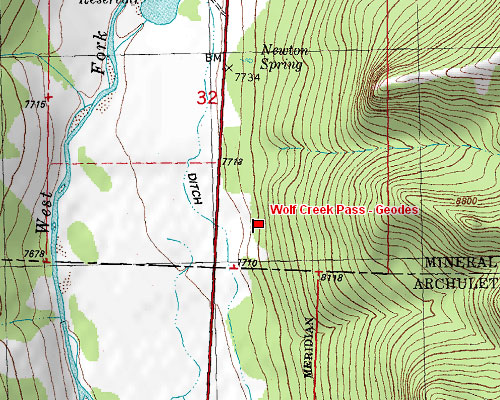

We said our goodbyes to Ouray this morning and headed south through Durango, then up US-160 towards South Fork. Along the way, we passed through Wolf Creek Pass, just north of Pagosa Springs where various geodes are to be found in a road cut of volcanic Basalt.

We managed to liberate lots of solid Agate geodes that may polish well, one nice Amethyst geode, a Chalcedony geode with paper-thin walls, and two geodes with thin white fiberous crystals within. We originally thought these were Natrolite, but I now think they are Mordenite, possibly growing over pale orange Heulandite crystals.

After this stop, we continued north to the Streamside Bed & Breakfast in Nathrop for our last three nights of vacation.

October 9th

The spot where we stayed is literally at the foot of Mount Antero, a famous Aquamarine locality. However, Antero is 14,269 feet, and the collecting area is only a couple hundred feet below the summit. This might be something we’d try in July, but not mid-October!

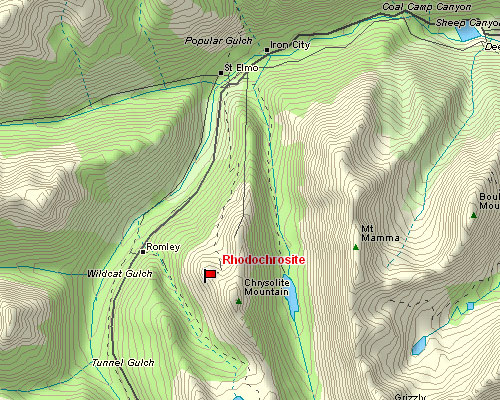

Instead, we drove west for a few miles to the semi-ghost town of St. Elmo (lots of old buildings, a few scattered residents), then a bit south to the Mary Murphy and Pat Murphy mines.

This was cold and windy enough, at just over 12,300 feet. The dumps had tons of Galena, a decent amount of Rhodenite, a few small crystals of light pink Rhodocrosite, and one nice piece of Azurite (at least it seems we found the only one).

Mary & Pat Murphy Mines

View from below the Dumps

Road Down from the Mines

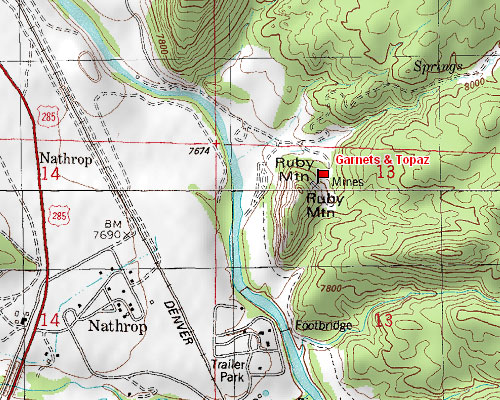

We then came down from the mountains and over to a small hill of Rhyolite alongside the Arkansas river, just outside of Nathrop. Small vesicles in the banded Rhyolite contain small but perfectly formed Spessartine Garnets, and even smaller Topaz crystals.

We did find quite a few garnets, the largest about 1mm, but perfect dodecahedrons ranging from gemmy pale orange to deep red. The Topaz crystals, if present, must be virtually microscopic – we found no trace of them.

October 10th

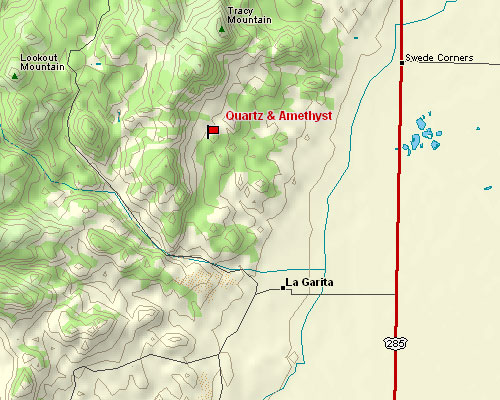

Our last day in Colorado we only hit one rockhounding site ’cause it was quite a drive from where we were staying – about two hours south near the small town of La Garita.

The Crystal Hill Mine was originally a Gold mine, but by following veins of Quartz in the volcanic breccia, you can eventually find vugs containing water-clear Quartz or Amethyst. It is hard-rock mining though, and we called it quits after uncovering one small Quartz-filled cavity. There is plenty of Manganese ore in the area, so we weren’t too surprised to find Dendritic Pyrolucite.

There must be someone raising Llamas or Alpacas on a ranch just below the mine area because this wildlife definitely seems out of place here.

Non-local Wildlife